Now this is really scary.

It’s Sunday morning, June 30th, and I’m sitting in my apartment in Munich when I catch wind of a hurricane brewing near the southern Windward Islands. At first, it’s just background noise, but then I dig into the details—checking NOAA’s hurricane center, tracking the storm’s path—and that creeping feeling of dread settles in. I realize that JACE might be right in the crosshairs.

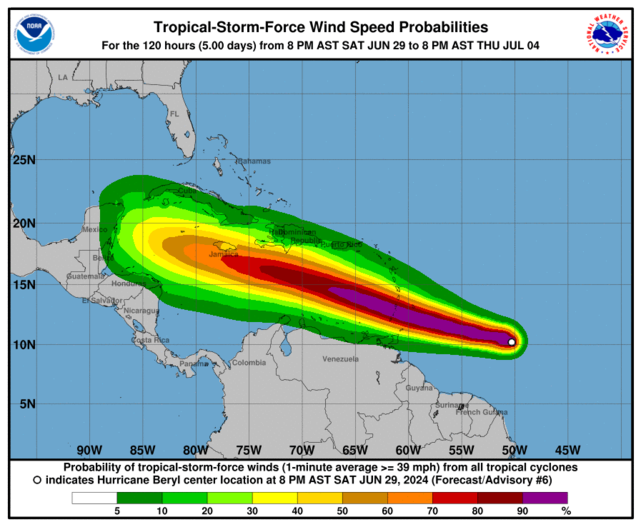

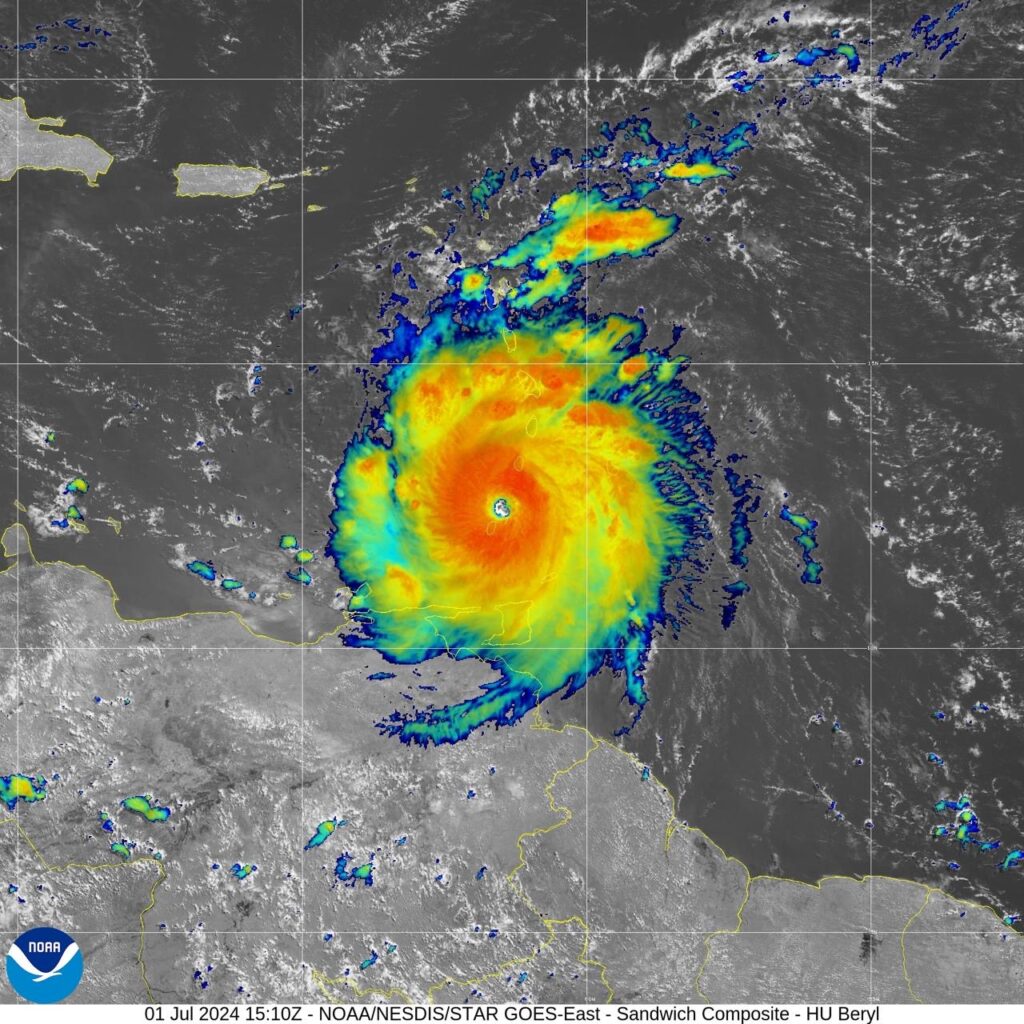

Hurricane season officially starts tomorrow, July 1. And ‘Beryl’—already the second (hence the B) named tropical depression in the northern Atlantic—looks like he’s about to break some records. Beryl will go on to become the second earliest category 5 hurricane, and, just for good measure, the southernmost storm of that intensity ever recorded.

Let me be clear: Grenada is supposed to be hurricane-safe. In over a hundred years, it’s taken only four direct hits, and none as powerful as what Beryl is shaping up to be. The worst they’ve seen was back in 1955—Hurricane Janet, a category 3 storm. That’s why boat insurers consider Grenada a safe harbor for the summer season. And that’s why JACE is there. I mean, really—after everything I’ve read and heard about how to keep a boat out of harm’s way during hurricane season, here we are, not even a day into it, and a monstrous category 5 is barreling straight toward us. Someone pinch me—this can’t be real, right?

But it is.

As I dig deeper, the dread grows. I start texting Brad and some of the locals I know to see how they’re holding up. Everyone’s fine, hunkered down in their homes, but the news isn’t reassuring. Yes, Beryl is a beast, and yes, he’s headed straight for Grenada. Brad was aboard JACE a few days ago, took down the sun covers, doubled up the mooring lines, secured everything as best he could. There’s nothing more to be done now. It’s all up to JACE—and that mooring—to weather the storm.

The forecast initially shows the storm curving north, away from Grenada. A flicker of hope. But as Sunday wears on, the path remains unnervingly straight. I find out that a large high-pressure ridge far to the north is blocking the usual Coriolis-induced curve. Oh, brother.

At some point, the fear becomes overwhelming, and I start seriously considering the possibility of losing JACE. I dig out the insurance papers, re-familiarize myself with the terms for named storms, but let’s be honest—no insurance could ever cover the emotional loss. I toss and turn all night, sleep eluding me.

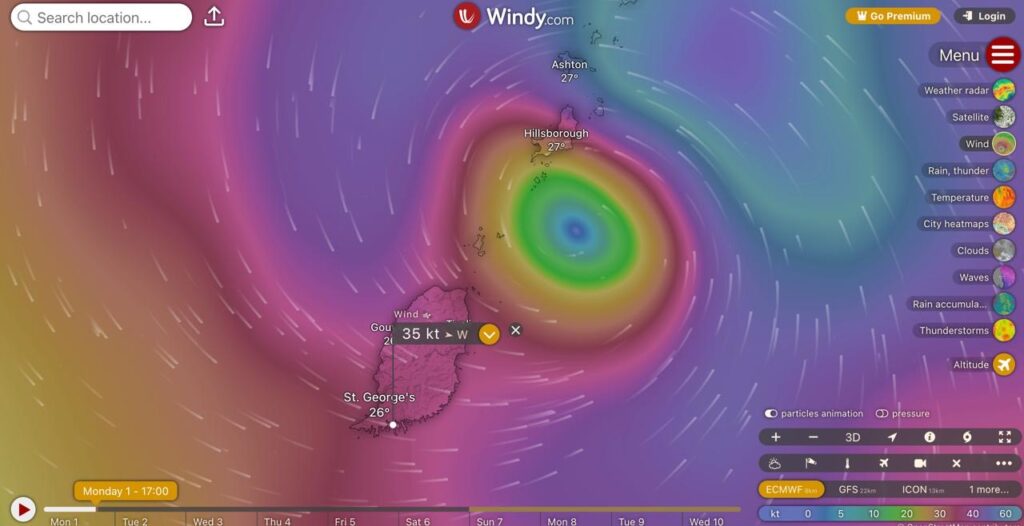

By Monday morning, Beryl finally veers a bit north. The eye is now forecasted to pass just north of Grenada, likely hitting Carriacou or Union Island—places close to my heart, as you might remember.

In the northern hemisphere, hurricanes spin counterclockwise, so the northern side of the storm is the worst place to be. On that side, the system’s forward motion adds to the rotational wind speeds, increasing them by another 20 or so knots. On the southern side, the opposite occurs, and thankfully, JACE is now positioned on that relatively “safer” side.

By 5 p.m. Munich time, Beryl makes landfall on Carriacou as a high-end category 4 hurricane. I later learn that the destruction is total. Terryl Bay, where I’ve spent so many nights anchored, and Union Island with its stunning Clifton Harbor and beloved kitesurfing school—everything is in ruins, if not completely wiped away. Many boats are lost, and my heart breaks for the wonderful people who call that place home.

JACE, however, is incredibly lucky. A few hours later, my buddy Mike, who rode out the storm aboard his heavy double-ender moored just behind JACE, sends me a video. The next morning, I get a photo of JACE still at her mooring, basking in the sun, looking as if nothing had ever happened. Amazingly, as I learn over the next few days, everything aboard is fine, save for some shredded canvas. But that’s nothing. Just 50 miles further north, and it could have been a very different story.

What a close call.

My heart goes out to everybody who was impacted so badly by Beryl and also thankful it veered North and your friends and JACE are well.